“Recall, O Lord, what befell us, look and see our disgrace–our estate turned over to strangers, our homes to foreigners” (Megillat Eikha 5:1-2)”

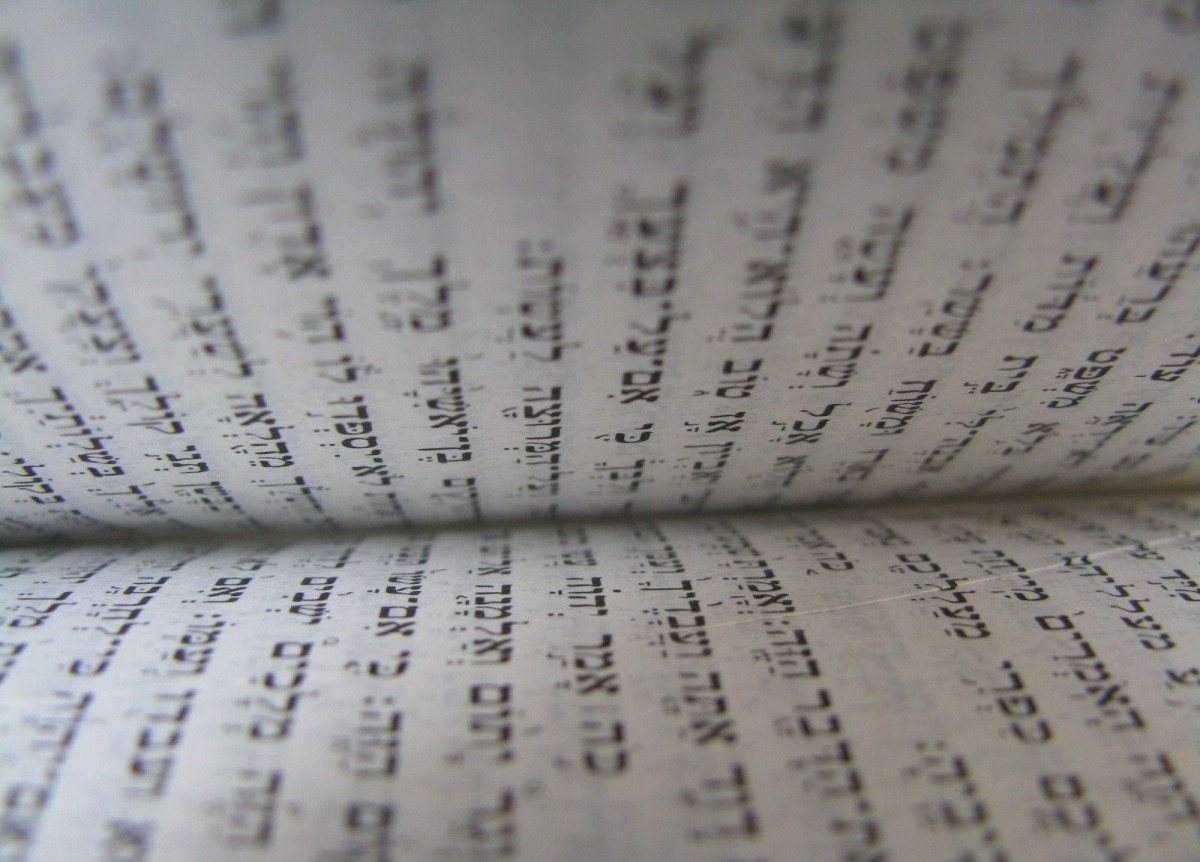

The final chapter of Megillat Eikha is about return and memory. The narrator opens by asking God to recall the events in Jerusalem, and ends by asking that God let them spiritually and physically return. Generations later, after a second Temple was built and destroyed, our rabbis continued to make similar pleas to God, only over time the actions the rabbis proscribed include more about remembering the temple, even as they longed to rebuild it. The Talmud states:

And the Sages say: Whoever performs labor on the Ninth of Av and does not mourn for Jerusalem will not see her future joy, as it is stated: “Rejoice with Jerusalem and be glad with her, all who love her; rejoice for joy with her, all who mourn for her” (Isaiah 66:10). From here it is stated: Whoever mourns for Jerusalem will merit and see her future joy, and whoever does not mourn for Jerusalem will not see her future joy” (Babylonian Talmud, Taanit 30b).

Traditional Judaism never lost the aspiration to rebuild the Temple, as traditions ranging from breaking a glass at a wedding to concluding the Pesah Seder implicitly and explicitly alude to this hope. At the same time, the command to remember remains, and this might seem odd the longer we go without a third Temple, to say nothing of the Messiah. What this suggests to me is that the rabbis made the choice that we must emphasize the story to compensate for lack of evidence. We have little reason to believe that a third Temple will be rebuilt after two thousand years (modern messianism notwithstanding), but, on Tisha B’Av, we are challenged to recognize that the facts do not always matter.

As a rabbi who does leadership development, I will admit that I am a split personality when it comes to the gospel of metrics. On the one hand, I believe that organizations fail to make evidence-based decisions time and time again; the first article I wrote as a rabbi was called “Moneyball Judaism” for that reason. At the same time, Judaism is not only a religion of the head, but of the heart, and anyone who denies the role of emotion in how our Judaism came to be is selling themselves a lie. Facts versus feelings is not a tension to resolve, but a polarity to manage.

Dara Horn captures this tension in her recent novel Eternal Life, which tells the story of Rachel, the mother of Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakkai, the sage credited with creating the yeshiva, the foundational institution of rabbinic Judaism. In a dramatic exchange between Yohanan and his mother, she asks Yohanan why he did not try to save the Temple itself. The passage states:

Mother, don’t you understand? When Vespasian asked me what he could give me, I knew exactly what to ask for. I asked for permission for the Torah scholars to be protected near their garrison in Yavneh. That way, no matter what happened to Jerusalem, there would still be people who could teach the Torah in the future. That way the Torah would be safe.” “But you could have saved the Temple!” “I don’t think I could have done that. If God wanted to destroy the Temple, God would destroy the Temple. God destroyed the Temple before”…“You’re like a child! You saved your favorite book!” “Yes! Because nothing matters but the story!” (Dara Horn, Eternal Life, 205-206).

Is Yohanan right that nothing matters but the story? I’m not sure, but this is the question that Jews grapple with each year on Tisha B’Av. Generations upon generations have passed since the destruction of the Second Temple, and what drives our connection to this physical place is not that any of us can say that we saw it with our eyes, but that we heard that story, felt the story’s impact, and passed it onto others. At the same time, what makes Tisha B’Av powerful is that it reminds us that telling the story is necessary, but not sufficient, to preserve Jewish tradition, for no story can take away the fact that there is no longer a Temple in Jerusalem.

Bill George writes in True North that “Leaders are defined by their unique life stories and the way they frame their stories to discover their passions and the purpose of their leadership” (xxvii). Sometimes, I find that synagogues are so wrapped up in the facts of the moment, everything from the budget obligations to the leaky roof, that they forget about the inspiration that makes those facts relevant, in the first place. Yet at a time when our institutions find many facts difficult to face, the only way to find new vitality and creativity is to momentarily forget the facts and focus on the story they seek to tell. Facts matter because they give us evidence, but stories matter because they give us hope. And in times when facts can discourage us from transformative work, hope matters a great deal.

May you have a safe and easy fast.